If any of those things happened, then the recipient was denied benefits for the reason “Failure to cooperate in establishing eligibility.” And because this system relied on breaking the relationship between caseworkers and the families they served, no one was there to help people figure out what was wrong with their application. So the people filling out the forms might make a mistake. The result of that was that these really complicated forms-which can be anywhere from 20 to 120 pages long including supporting documentation-people often make mistakes on them. And every time a recipient called the call center, they talked to a new person. So nobody saw cases through from the beginning to the end. So that’s why I looked at public services.Īnd rather than carrying a docket of families that they served, they responded to a list of tasks that dropped into a computerized queue. Internationally that would be in war zones. So domestically, that would be in programs that serve poor and working people or in communities of undocumented immigrants. We have a tendency to test these tools in environments where there’s a low expectation that people’s rights will be respected. And I think it’s really important to look at the places where these tools are actually already impacting people’s lives right now.

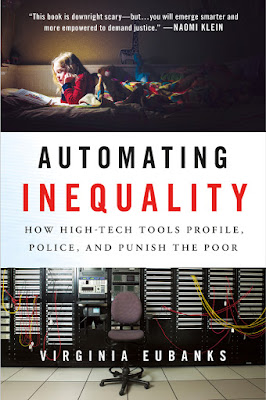

One is that when we talk about issues about automated decision-making or artificial intelligence or machine learning or algorithms, we have a tendency to talk about them in a very abstract way. Virginia Eubanks: These systems are really important to understand for a number of reasons. Why did you pick these cases, and what do they illustrate? Amanda Lenhart: In the book, you write about the “digital poorhouse” and discuss three different examples of governments using digital tools to manage access to social safety net benefits and services: a system in Indiana that governs welfare benefits, one in Los Angeles about access to housing, and one in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, that flags potential child abuse and neglect.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)